Every year, more than 33,000 Americans die from gun violence and if you think you hear about it in the news more frequently than you did when you were younger, you’re right. Since the 2012 shooting at Sandy Hook Elementary School in Newtown, Connecticut, there have been more than 1500 mass shootings, defined as four or more people being shot at the same general time and location. While many are still questioning if the United States has a gun problem, another question has been somewhat vacant from the forefront of the gun violence discussion. What happens to the unspoken community of mass shooting survivors each time another mass shooting occurs?

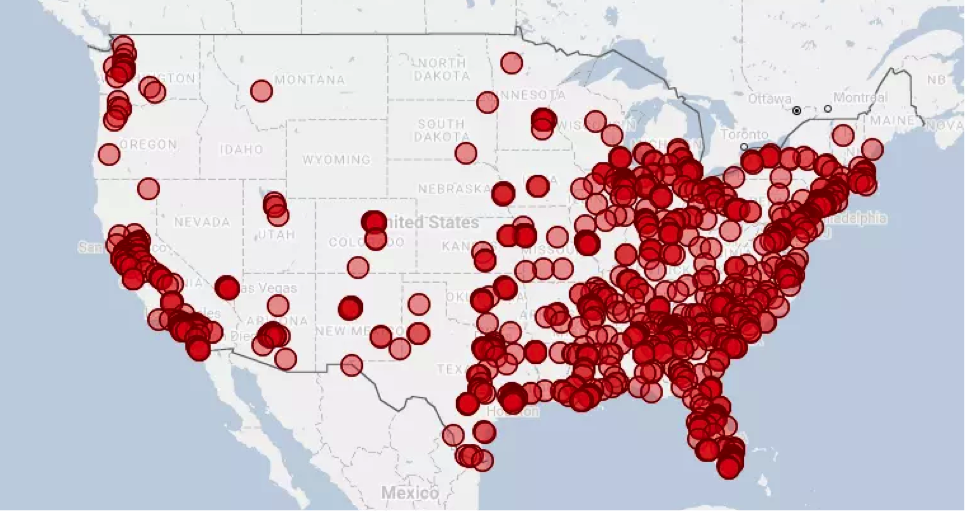

Soo Oh/Vox: Mass shootings since Sandy Hook

“There seem to be two main reactions: you want to get up and do something and other people just want to get away from it,” explains Bob Weiss whose daughter Veronika was one of six students killed in the 2014 Isla Vista, California shooting. He recalls the press immediately descending upon his family and a moment when he knew he needed to speak out on gun violence. “I was always on the side of more gun laws being safe and I didn’t have any prior experience as an activist in gun violence prevention, but when you get hit in the face with it like that, it’s life changing.”

The Monday after the Isla Vista shooting, on the other side of the country, Mary Ann Jacob and a group of survivors from Sandy Hook gathered to discuss their next steps. “We wrote a letter to other survivors in the building and 40 people showed up,” she said. “Everyone expressed the same need to do something.” Almost a year and half since 20 children and six adults were killed at their elementary school, they agreed that their voices needed to be part of the larger conversation on gun violence. “Different things felt right for different people. Everybody found themselves fitting in a way that worked for them personally.”

Lorenzo Basilio/The Bottom Line: Thousands gather in Isla Vista for a vigil the day after the 2014 shooting

Many survivors are empowered by their tragedy, inspiring dozens of organizations. Moms Demand Action, founded by Shannon Watts immediately after the Sandy Hook shooting, established a chapter in every state to demand what it calls “common sense gun reforms.” One year later, the grassroots organization merged with Mayors Against Illegal Guns to form Everytown For Gun Safety, the national non-profit working to end gun violence by educating policymakers, the public, and the media. No Notoriety, founded by Tom and Caren Teves after their son Alex was killed in the Aurora, Colorado theater shooting, works to eliminate the name and likeness of mass shooting killers in the media, and instead focus on victims, heroes, and survivors given the fact that infamy and notoriety is a proven motivational factor in mass murders. These and many other groups are a driving force in the gun violence prevention movement, but they all face a $30 billion gun industry and one powerful adversary – the National Rifle Association.

“We’re a gun-crazy culture and the majority of sane people realize this, it’s just that the gun lobby has such a grip on government with money that pours in from the industry and the NRA,” says Weiss who has partnered with Everytown and The Brady Campaign in the hopes of preventing other families from experiencing the same loss. “We don’t have the resources or the single voice that they do. We have 100 little organizations; they have one powerful voice that speaks consistently.”

Jacob, in Sandy Hook, who identifies as both a Republican and gun-owner, agrees. “All surveys show 60 percent of NRA members believe in background checks. We’re allowing the top of the NRA to dictate policies and discussion because of money…I believe in the second amendment, but I believe it comes with great responsibility.” She doesn’t view gun control as a political issue, but rather one of public health.

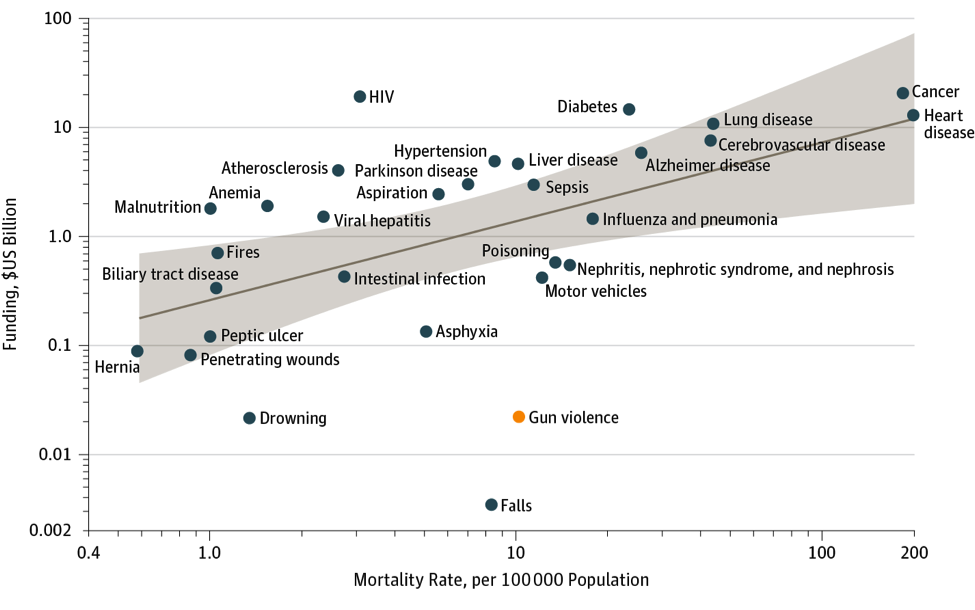

Unlike other epidemics, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) have effectively been barred from studying firearm violence, which, advocates argue, already receives disproportionately low funding.

“There’s actually a block on federal funding of research on gun violence,” explains Weiss. The 1997 Dickey Amendment prevents the CDC from using available funds “to advocate or promote gun control” and has been reauthorized annually by Congress for 20 years.

“Fewer people die in cars because of graduated licensing laws, parents, and driver’s ed.,” says Jacob. “Just because one person doesn’t drive the speed limit doesn’t mean we shouldn’t follow speed limit laws.”

JAMA: Funding for Research on Leading Causes of Death from 2004-2015

Injured in 2007 after jumping out of a classroom window to escape the shooter at Virginia Tech, Jeff Twigg also wants gun reform and is perplexed by the double standard applied to gun violence research and preventative legislation. “We try so hard to stop terrorism, car crashes, any number of traumas that are caused by people but for some reason we cannot try and stop this one. It doesn’t make any sense,” he said.

In a recent USA Today article, Twigg spoke out on the importance of voting against current legislation like the SHARE Act and the Hearing Protection Act, which would reduce silencer safety laws, making it easier for silencers to be purchased without a background check. “If you are an upstanding citizen who is hunting or using a gun for self-defense, you want people around you to hear the gun,” says Twigg.

Hearing gunshots before the shooter reached his classroom saved his life much like it did for many in Las Vegas, including Robin Brown who recalls the commotion after hearing the gunshots that prompted everyone around her to drop to the ground to take cover. “It sounded like a firecracker,” she said. “A lot of people did realize they were gunshots. It kept repeating – 40 shots, then it would stop 10 to 20 seconds in between, then go again.” Brown was in the crowd at the Route 91 Harvest Festival last month and says her concept of time has changed dramatically and she continues to process feelings that unexpectedly arise each day. This is one of myriad emotional responses when something like a mass shooting occurs.

“People have this set of confused emotions around how to feel. Are they traumatized? Angry? Do they just want to forget? A lot of times they don’t want to engage or talk about it. People can really shut down,” says University of California, Santa Barbara psychologist Dr. Turi Honneger. ”I think what becomes more emotional and potentially angering is the larger national conversation around these issues.”

There have been nearly as many mass shootings in 2017 as there have been days in the year. As each event was covered in the news cycle, uproar ensued and politicians sent their “thoughts and prayers” to victims. After the recent shooting in Northern California that killed six and injured 12 including multiple elementary school students, the Sutherland Springs shooting that killed 27 and injured 20 in a church, and the most deadly shooting in American history that killed 59 and injured 441 Las Vegas festival-goers, an unspoken community of mass shooting survivors watched as the familiar voices of two juxtaposing camps—“End Gun Violence” versus “Stop Politicizing Tragedies”—were heard loud and clear across the echo chambers of the internet.

While gun rights advocates often state the immediate aftermath of a shooting is not an appropriate time to push a political agenda, the growing community of mass shooting survivors has been waiting for action and continues to mobilize in hopes of preventing future tragedies.

“If me and all of the people who are angry right now take our voices and share that with our elected officials, that’s huge,” says Brown.

Still, it takes emotional labor every time a survivor turns on the television or goes online after a mass shooting and witnesses the all too familiar imagery of another community impacted by gun violence. Immediately after the Las Vegas shooting, a Facebook group for survivors was created. Brown is one of many who joined the digital space appreciating the virtual community where people post positive messages and raise money for victims and their families.

“I’m in the club that nobody wants to belong to. They’ve been really helpful to me and I try to help the new members,” says Weiss in regards to the network of survivors supporting one another and working collectively to end the gun violence epidemic.

While cyclical media coverage triggers or re-traumatizes some, others are encouraged because it also can simultaneously build momentum. “Our country doesn’t change overnight. It’s a long cultural shift and we have to think about all the ways we can make a difference,” says Jacob. “Unless you’re willing to stand up and speak up, things aren’t going to change.”