Piles of flyers in English, Chinese and Spanish were handed out with an arresting question at the beginning, “Are you sick of waiting while your boss gets away with stealing your wages? ” To address this problem, also known as wage theft – over 30 low-income workers gathered outside the Department of Labor on Nov.12th to urge the Department and Governor Cuomo to enforce labor law.

“The Department is sending out a message to employers that stealing from your worker is OK,” said JoAnn Lum, the director of the National Mobilization Against SweatShops(NMASS), a workers membership organization dedicated to protecting labor rights. “And the DOL’s new policy is simply worsening the situation.”

In May 2013, the Department of Labor decided to reduce its investigative scope period from six years to three years to break the rising backlog of wage theft investigations. It is also closing cases under special circumstances, for example cases of claims less then 500 dollars. The policy is intended to expedite the proceedings of pending investigations but it is considered a huge loss for workers who have been waiting for years to get their stolen wages.

“My case went beyond the three-year-scope and the Department refused to take it to trace back my stolen wages for the previous six years,” said Qing Yang in Mandarin. Yang used to be a doorman but was fired after his complaint to the employer. “The department only accepted my case on the grounds of unlawful termination and vacation bonus in arrears; the amount of compensation for that is like… nothing. ”

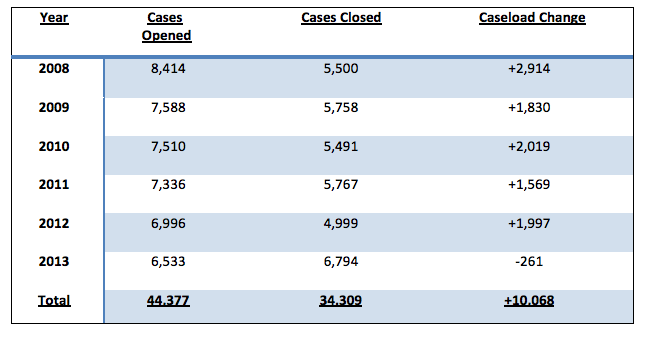

The new policy was meant to be a solution for the rising number of investigations filed by workers against their employers and shorten their time for waiting. It did decrease the number of cases. According to the latest statistics from the State’s comptroller, the number dropped in 2013 while it had been increasing dramatically ever since 2008. But the overall volume of cases is still incredibly high. As of Aug. 26, 2013, the Department of Labor had a caseload of 17,191 cases, of which 12,938 cases (75 percent) had been open more than one year. In contrast to the huge caseload, there are only 98 investigators, each responsible for an average of 95 active investigations.

Numbers each year of Cases of Wage Theft Investigations in Department of Labor. From New York State Office of the State Comptroller’s report, Wage Theft Investigations.

“When I filed a complaint to the Department in 2007, they said they would call me every month to follow up. But they never called,” said Carlos Rodriguez, a former worker for Domino’s Pizza who worked more than 66 hours a week but only got paid for 40 hours with a wage of $4.40. “When I finally heard something back in 2011, I was told my case was closed as my employer settled with the Department for $365. ”

Domino’s Pizza was unavailable for comment.

A long waiting period is common among workers like Rodriguez. “Many workers wait for five to six years to get a response for their cases,” said JoAnn Lum. “The department is carrying out the new policy only to move faster in dealing with these cases.” Lum expressed that her frustration at the way the Department tried to solve the problem.

But Department of Labor responded that their work has actually been pretty effective. “The department had a record year in 2013 when it recovered and distributed nearly $23 million to more than 12,700 individuals. The agency is on track to far surpass last year with more than $16 million in wages recovered in just the first 6 months of 2014,” said Cullen Burnell, DOL’s press officer in an email.

Despite the progress, it’s hard to ignore the piling cases on DOL’s desk and the scene behind it – the “epidemic of wage theft”, as Jum would call it. According to a research conducted by the Center for Urban Economic Development in 2009, in New York, Chicago, and Los Angeles, the total annual wage theft from low-income workers in these cities reached $3 billion. The average loss per worker was $2,634 for one year, out of the total annual earnings of $17,616.

“I was paid only $1.25 per hour while the State’s minimum wage is 8 dollars,” said Adolfo Lopez who used to work as a delivery man for a restaurant in NYC. “I worked 72 hours a week but only got $90 back. And New York is so expensive, the food, the transportation, everything.”

After over five months of protesting, National Mobilization Against SweatShops(NMASS) is now prepared to file a lawsuit against the Department of Labor. The National Center for Law and Economic Justice is providing the workers legal assistance and filed a letter on their behalf to the Department.

“We are ready to sue them, up and down,” said JoAnn Lum. “If you also suffer from wage theft, let us know and join us.”