Brown wooden desks, shimmering chandeliers, ceilings made of reclaimed tins; you ordered a hot drink and soon arrives the waiter with an old-fashioned enamel cup – can you imagine such a cozy place is actually a hamburger restaurant? The place is called Bareburger, a chain famous for its organic food including burgers.

“Customers come in expecting A, to get a good burger; B, an organic burger which is seen as a healthier option,” said Cordelia Tai, a waitress of three years at the Bareburger in LaGuardia Place.

By clinging to organic and natural ingredients, this New York based chain distinguishes itself from other burger joints and is gradually wining national popularity – its 29th store is soon to land in Chicago. Seven new restaurants opened in 2013, four in 2014 and three more slated to open this year. Bareburger’s rapid growth serves as an interesting footnote to the organic food phenomenon, an illustration of how the concept of “organic” has been broadening and converging with what used to be regarded as “junk food”.

A Bareburger restaurant in LaGuardia Place, with its unique shop sign saying “organic salads, organic sandwiches, organic shakes.” Sept. 16th, 2014 (Siyi Chen)

“Bareburger is a reaction to what guests wanted,” said Debra Jans, Bareburger’s Chief Learning Officer. “In the last few decades, the U.S. has been taking a closer look at the way we’re producing our food.” Debra expressed that the rise of Bareburger is part of the larger trend of going organic.

Bareburger is not alone. Now in the New York City, there are organic ice creams – one of the most famous brands being Blue Marble; and even organic tobacco – hipsters in Brooklyn are said to be fervid fans of American Spirit, the only cigarette made with USDA-certified organic tobacco.

Behind the “invention” of so many new genres of organic food is the rapid growing industry. The sales of organic products rose to $35 billion in 2013, representing a 12 percent annual growth – the fastest rate amidst the last five years, according to data from Organic Trade Organization. The number of USDA certified organic operations also increased to 18,513 in 2013, indicting a nearly 245 percent increase since 2002, according to the USDA’s latest annual census.

However, the “definition” of organic has also changed along the way: the USDA’s list of non-organic materials allowed for use in certified “organic” products has grown simultaneously with the industry. To comprehend the list, one has to go through piles of documents and a maze of complicated terms. Nevertheless, a 2012 report in the New York Times made it through the maze and discovered that non-organic substances on the list rose from 77 to 250 during the ten years between 2002 and 2012; among them are ingredients like Carrageenan and Ascorbic acid. Media have questioned whether organic has been “oversized” by the influences of the intimate relationship between big agricultural corporations coveting the lucrative business, and the National Organic Standards Board, which advises the USDA in “defining organic”. An NPO called Cornucopia Institute examined this delicate relationship in a white paper published in 2012 claiming it to be, “The Organic Watergate”.

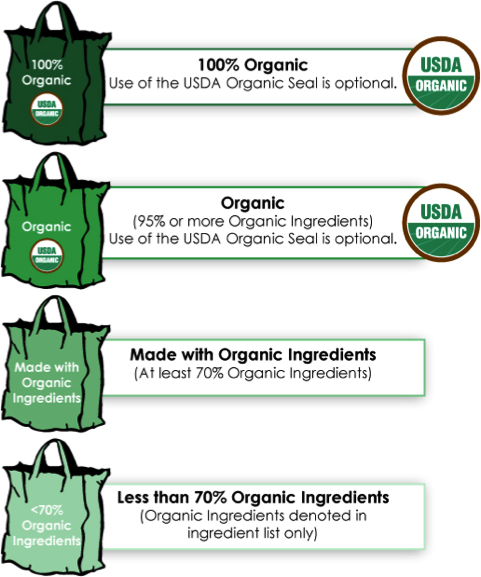

USDA’s four types of organic labels. Note that many products with “organic” label, especially processed food are not totally free from non-organic substances. Only “100% Organic” means truly organic.

Picture from the website of Agricultural Marketing Service, USDA.

While the definition of organic keeps “broadening”, customers seem to be unable to keep up, resulting in a gap between their understanding of organic and what it really means. Most regular shoppers at Whole Foods Market in Union Square were surprised when told the four types of labels and the difference between “organic” and “100% organic”. “I know there are two or three types of labels, but I didn’t know there are four!” said one shopper.

The gap between consumers’ understanding and reality not withstanding, an organic label clearly influences consumers’ perception – sometimes creating a “health halo effect”. In an experiment in Ithaca, New York conducted by researchers from Cornell University, 115 people were asked to rate the taste and caloric content of three pairs of food products. All pairs were identical but one of each was labeled “organic”. The researchers found that the label created bias: participants believed the products labeled organic were more nutritious and less flavorful and were willing to pay more for the organic food.

Such a “halo effect” seems to affect consumers’ choices when it comes to junk food. If there is an option for an organic version of cookies, burgers, donuts etc, would you go for it? “Sure. Why not? As long as they [the food producers] are telling the truth,” said Robert Scannicchio, a loyal fan of organic food who was comparing different cookies in the Whole Foods Market when interviewed.

Organic onion rings sold at Whole Foods Markets, a supermarket chain specializing in natural and organic food. Sept. 16th, 2014 (Siyi Chen)

While consumers are attracted by the magic word “organic”, experts warn that rather than necessarily meaning foods “healthier”, organic is more about production values like fewer pesticides and more sustainably agricultural practices. “They are worth buying for that reason alone, ” said Professor Marion Nestle from the Department of Nutrition, Food Studies, and Public Health at New York University in an email reply. “An organic junk food is still a junk food, and putting in organic ingredients does not convert it to a healthy food.”

Despite what the nutritionists say, Americans still love fast food. The growth of US fast food market is likely to register a CAGR growth of around 4% from 2011 to 2014, according to the US Fast Food Market Forecast to 2014 from Research and Market. Slapping an organic label on it perhaps makes it a little easier to swallow.

Even within the fast food industry, there’s also a trend of going “healthier”. Statistics from analysts at Janney Capital Markets predicts that in 2020 fast food joints like McDonald, Burger King will be replaced by healthier counterparts — like Chick-Fil-A and Chipotle, the so-called “fast-casual” restaurant.

“At the end of the day we’re still burgers and fries,” says Jans, Bareburger’s Chief Learning Officer. “We’re not saying you should eat burgers and fries everyday. But when you want to take your kids, your family for an occasional treat, you’ll have a place to go, where no food there is full of ingredients whose names you don’t even know how to pronounce.”