A bill to enable sick or deceased vendors to transfer vending licenses to family members was recently introduced in the New York City Council. With a limit of 853 general vending licenses issued to non-veterans in NYC and thousands on the now closed waiting list, the bill intends to help a certain group of people in urgent need of licenses. However, in Elmhurst, one of the most vendor-intensive areas in NYC, many vendors have been living in the grey areas of license regulation for years. It is not yet clear how much the new bill would affect their life.

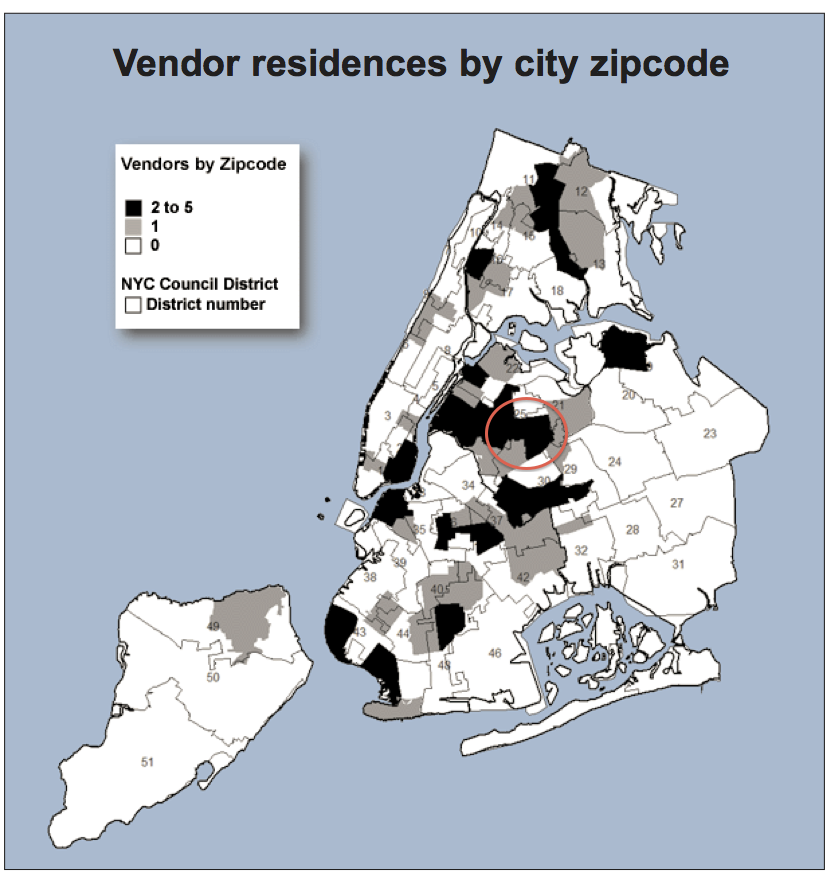

From a 2006 report conducted by Street Vendor Project. Elmhurst in the lower part of District 25.

The bill, introduced by city councilwoman Margaret Chin, who represents Lower Manhattan, was prompted by the case of Chun Yin, a woman arrested 11 times by NYPD for taking care of her husband’s vendor business in Chinatown when he was too sick to work. Yet this bill, which is likely to change the destiny of many families like Yin’s, doesn’t seem to appeal to many vendors in Elmhurst, who have already been running a “family business” for years without incident.

One couple, selling bags outside the Macy’s at the Queens Mall have been working together for over 21 years. Most of the time the wife looks after the cart even though the husband holds the license. Such an arrangement is technically illegal but, so far, as long as the husband shows up when the police come to check the license the couple has not been getting into trouble. Due to the sensitive matter of the issue, the couple refused to give their names.

Apart from sharing a license, there are also vendors who don’t even have a license, transferable or not.

“We didn’t apply for it,” said Ms.Ge in Mandarin, who did not want her full name used because of legal issues, referring to the vendor’s license. “My friend says it’s going to take years and it’s almost impossible [to get a license] now.” Ge came to the U.S. seven years ago with only three years of primary school education making her cart a necessity to support herself. “I’m doing an honest business. [Unlike other vendors] I pay tax,” said Ge with pride. “I show my tax ID to the police [when they check my license] and often, they would just let me go. ”

Despite the lack of a license, Ge has been able to establish a successful “family business” like many vendors in Elmhurst. “The police know my mom and me now. So even if she’s absent and I am looking after the stall, they won’t find fault with me,” said her elder daughter who smiles shyly every time she finishes a sentence.

Nevertheless, a few steps from the couple selling bags outside Macy’s, another young vendor called Tuan tells a different story about his licensing experience. While other vendors wait for years to be licensed and face a cap of 853 licenses to be issued, Tuan’s application was approved within a few days because he is a veteran. In addition he pays $10 for the annual renewal fee of the license whereas other license holders must pay $210. The ease that veterans can get the coveted licenses has created another grey area for vendors in Elmhurst.

Retired veteran George, also a vending license holder now cooperates with a rug dealer “on commission”. “This guy (the dealer) hires me and pays me about $100 bucks everyday,” said George, who served the army for 7 years and survived the Vietnam War. Since George’s “boss”, the rug dealer doesn’t have a license, George’s responsibility also includes “coordinating” the police with license checking, besides sitting next to the cart and talking with customers.

With many vendors struggling to get a license or to live without one, the Street Vendor Project, a non-profit organization and also a major supporter of the new bill, acknowledges that this bill can only help “a relatively small group of people”. “ The real or broader solution lies in raising the cap of licenses [issued to non-veterans],” said Matthew Shapiro, of the Street Vendor Project. To achieve this goal, the Project has been carrying out campaigns since this spring to initiate a new bill, according to Shapiro. “Hopefully it will come out within a few months.”