Savona Bailey-McClain is considered as one of the best tour guides in Harlem by the platform Airbnb. “I have something in common with Christopher Columbus,” said the 54-year-old woman laughing to a group of Spanish and Israeli tourists that she just met at the corner of Edgecombe Avenue and 142nd Street. “He was born in the city of Genova but raised in the city of Savona and that’s my name!” smiled Savona Bailey-McClain.

Savona Bailey-McClain is considered as one of the best tour guides in Harlem by the platform Airbnb. “I have something in common with Christopher Columbus,” said the 54-year-old woman laughing to a group of Spanish and Israeli tourists that she just met at the corner of Edgecombe Avenue and 142nd Street. “He was born in the city of Genova but raised in the city of Savona and that’s my name!” smiled Savona Bailey-McClain.

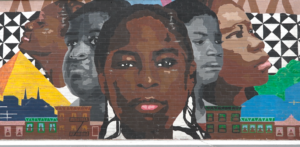

The native New Yorker and African American has been living in Harlem for 40 years becoming a community organizer and art curator, both in Harlem. Two years ago, she started conducting tours once a week to spread the word about how great she thinks Harlem is. Every week the “natural, eloquent and classy storyteller”, as described by tourists, explores with them key places in Harlem for $40 a ticket, like the 19th century row houses or the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture. Such places allow tourists to not only understand Black American history but American History. “There has been a lot of miscommunications about the contributions that Black people have been given in this country,” said Bailey-McClain. “Changes are going fast so we need to talk about that before it’s too late.”

Harlem is often considered the African American Capital. In the 1920’s, this is where the intellectual, social, and artistic explosion, known as the “Harlem Renaissance”, took place and kindled a new Black identity. Decades later, in the 1950’s, the African American community exploded to the extent that they were ninety-eight percent of Harlem’s population.

What about today? In 2017, Black people accounted for fifty-three percent of Harlem Central’s residents, according to data from the US Census American Community Survey.

What about today? In 2017, Black people accounted for fifty-three percent of Harlem Central’s residents, according to data from the US Census American Community Survey.

“The gentrification has changed the neighborhood,” said Tshombe Ra, Doctor in Africology and Harlem’s resident for 20 years. “It can be seen as a sign of progress for newcomers because of the new amenities that gentrification brings. However, the Black culture seems to be diluted.”

Another survey from the United States Census Bureau released last year, showed that out of the ten New York neighborhoods experiencing the fastest business growth between 2000 and 2015, Central Harlem had the biggest increase. “The Black identity is being stripped away,” said Ace Hope, a Kitchen Clerk in Central Harlem for 8 years. “You can’t really feel the culture anymore. A lot of companies like Whole Foods Market have come in along 125th Street from St. Nicholas Avenue to Malcolm X Boulevard. They took over those shops where you could find real black food and listen to black music.”

But for some residents, it’s not really an issue. “Recently, I have seen a lot of restaurants getting the Parisian style and all that,” joked Beverly Ried, a 54-year-old retired mother of four and grandmother of three. She has been living on 133rd Street for 40 years. “But I love the fact to be surrounded by people from all spectrum. The change never has been an issue for me because I can still feel the community spirit in Harlem.”

This community spirit also seduced Joshua Hakimini, 51. The father of two takes care of a community garden located on 134th Street. He has been living here for 18 years and now he is worried about the future. “Development doesn’t care about who lives here or not, what ethnicity or what culture and it’s a pity,” he said. Hakimini, from Iran, used to be “the only white” in his building but not anymore. “You can try to hold but at a certain point, you will be pushed out. I am going to be pushed out because it’s becoming too expensive.”

A study released in February 2018 stated that Northeast Harlem is one of the most gentrified neighborhood in the United States. The research team from RentCafé, a nationwide internet apartment listing service, analyzed data from the 2000 Census and the 2016 American Community Survey. From 2000 to 2016, Northeast Harlem’s median income has grown by 32 percent and its population of college-educated residents by 168 percent.

Some habitants have already been forced to leave the neighborhood according to residents — to the Bronx, New Jersey or Atlanta — but others who have stayed are helping to maintain Harlem’s Black identity. Three years ago, While We’re Still Here, a historical preservation society, was founded to document and preserve the historic homes of Black Harlem. Since 2013, Jacob Morris, a former real estate agent, has been fighting to rename streets after black women.

However, some residents think more needs to be done. “There are good initiatives but it’s not enough to stop Harlem turning into a white neighborhood,” said Michael Henry Adams, a Harlem Historian, who is writing a book about gays and lesbians in Harlem between 1950 to 1985. “There are beautiful historic churches being destroyed to be replaced by buildings for rich people.” Adams added: “To protect the Black identity in Harlem, a residential and commercial rent control should be established as soon as possible.”

Meanwhile, this past Spring, the City’s Landmarks Preservation Commission created the Central Harlem historic district stating the designation is “a remarkable reminder of the significant role the African American community of Harlem.”