Youth Court hearing. Photo provided by Red Hook Community Justice Center

Daren John, 17, is a Judge, Juror and a Youth Advocate who has the power to decide what consequences his peers should take for their misdemeanors. He serves at the Red Hook Youth Court, a program managed by the Community Justice Center in an effort to keep young delinquents away from the adult courtroom.

“The positions are rotating and I’ve experienced all of them,” said John, a freshman at the John Jay College of Criminal Justice. “If you come to Youth Court everything happens off the record. So we allow you to deal with the offense without having to go to jail or any severe influence on your record.”

Youth Court is designed to be an alternative to the traditional criminal justice system. Teenagers from 13 to 18 years old are trained to handle low-level juvenile crimes involving their peers like larceny, truancy, possession or use of marijuana, which are referred to the Youth Court by the New York Police Department, the New York City Department of Probation, Family Court, or Criminal Court.

Photo provided by Red Hook Community Justice Center

After a case hearing, the jury of 8 teenagers reach a consensus and choose to sanction their peer to a certain number of hours of community service, apology letters, or workshops like behavior control or job readiness. Upon completion of the sanction, a young offender can then have his case closed with the Youth Court instead of going to probation or detention.

“It’s positive peer pressure in a sense,” said Gleacy Mejia, Associate of Youth Programs and Communications, who was a Youth Court member herself when she was in high school. “The process is not punitive at all. We provide services to help them instead of just harming them or making them have a record. We offer them a second chance.”

Second chances are being provided across the country as the US is locking up fewer young offenders than ever.

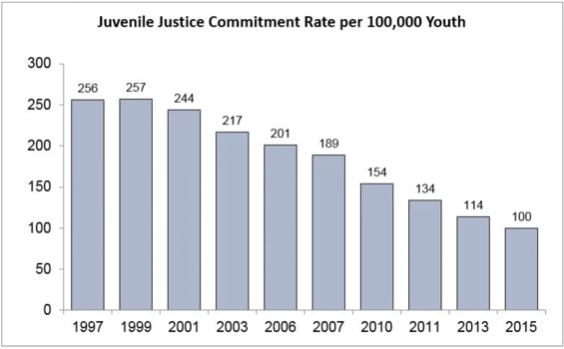

Juvenile incarceration rate has constantly fallen since 1997 and hit the lowest point in 2015, the most recent year available, dropping by more than 60 percent over the past two decades, according to the US office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention. Roughly one in 1,000 teenagers were confined in correctional facilities in 2015, compared to one in 400 in 1997.

Source: US office of Juvenile Justice and Delinquency Prevention

After the late 1980s and early 1990s, when there was a dramatic increase in juvenile crimes, state legislators across the country began to argue that young offenders are better served if they are treated as youths in the courtroom, separated from adults, and that they deserve a chance to outgrow delinquency and criminal behavior.

“A young person’s mind is not fully developed until they’re 25,” said Sabrina Carter, Associate Director of Youth and Community Programs at Red Hook Community Justice Center. “When a 16- or 17-year old does something wrong as a kid, they’re charged as an adult now. It’s really good and important that people are trying to change that.”

To allow youths under 18 years old to stay as juveniles in the eyes of the court, an increasing number of states have raised the maximum age for juvenile court jurisdiction.

According to the 2011-2015 trend report from the National Conference of State Legislatures, Connecticut started the trend of raising the age in 2007, when the state legislation returned 16 and 17 year olds to the juvenile court’s jurisdiction. Now 41 states set the maximum age at 17, 7 draw the line between juvenile and adult at 16 and only two states-New York and North Carolina-still set it at 15. In 2015, both states introduced measures to raise the age from 15 to 17 but both bills failed.

While New York continues to lag behind the reforms, what advocates argue makes the situation even worse is that the majority of the 16- and 17-year olds who are arrested and face the possibility of prosecution as adults in criminal court commit relatively minor offenses that do not pose severe risks to the public safety.

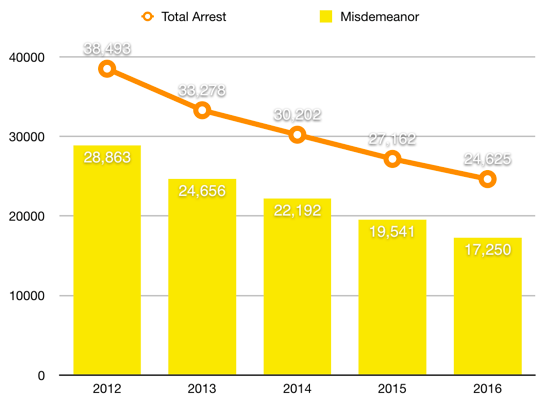

More than 24,000 16- and 17-year olds were arrested in 2016 in New York State and more than 70 percent of those arrests were for misdemeanors, according to the arrest report from New York State Division of Criminal Justice Service in February 2017. However, the report also shows that the total number of arrests among 16 and 17 year olds has been declining since 2012 by more than a third.

The rate is expected to drop even more since Governor Andrew M. Cuomo finally signed “raise the age” into law in New York on April 10 this year. By October 2019, New York State will no longer automatically prosecute all 16- and 17-year olds as adults.

“With the raise-the-age act, we expect an influx of referrals to the Youth Court,” said Carter. “We’ll definitely be affected in a good way.”

The Youth Court program was first launched in Red Hook in 1998 by the Center for Court Innovation, a non-profit organization woking in partnership with New York State Unified Court System. Now the program has expanded into Brownsville, Harlem, Staten Island and most recently Queens in 2012.

“It’s been a beautiful experience working with the youth,” said Wesley Thompson, Program Developer of the Queens Youth Court. “I definitely hope the raise-the-age act will turn more cases from the traditional criminal court to Youth Court.”

Advocates argue that compared to the traditional courts like Criminal Court or even Family Court, Youth Court can better relate to young offenders under the age of 18 and open them up to talk about the root of their problems.

“Lots of times there are certain circumstances behind the action, so you can’t just automatically jump on them and judge them,” said Morgan Scott, 17, member of the Red Hook Youth Court. “The main purpose is not to punish someone for doing something. Our steps are essentially to help them to identify what they did that was wrong, and ways to avoiding getting into that kind of situations again.”

That’s probably why it’s very rare for Youth Court respondents to commit a second offense. “We hear about 150 cases a year and for the past five years only two or three kids came more than once,” said Mejia. By contrary, studies done by the US Center of Disease Control and Prevention have found that young people transferred to the adult criminal justice system are 34 percent more likely to be re-arrested for violent and other crimes.

“It’s based on the broken window theory,” said Carter. “When you can get a handle on the smaller crimes it’ll prevent bigger crimes from happening.”