Retired nurse, Beverly James leads A.S.K. for your life workshop at St. George’s Episcopal Church in Hempstead

Racial disparity in medicine has been a problem in the United States for a very long time. Back in 1984, the US Department of Health and Human Services published a study that found that disproportionately “the burden of death and illness experienced by blacks and other minority Americans,” far exceeded the nation’s population. Since then, studies into medical outcomes in the United States have repeatedly shown that black Americans suffer worse medical outcomes than any other group. That disparity becomes all the more devastating when it’s not one life at stake, but two.

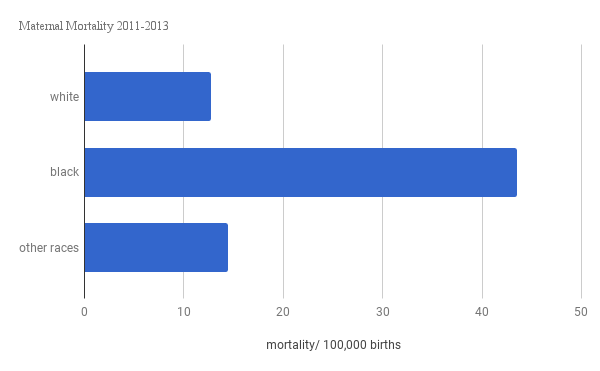

Often depicted as a joyful experience, childbirth has very real risks, especially if the mother is black. Maternal morbidity in the United States has been rising since the mid 1990s, and this increase in maternal fatalities has disproportionately affected black women.

“For virtually all health outcomes related to pregnancy, there is this huge divide,” said Kerri Wade, director of communications for the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine. “And really it’s black women who bear the burden of poor health outcomes.”

Many factors contribute to the disparity, but the solution depends on who you talk to. Patients and advocacy groups point toward racial bias, while medical establishments are more likely to point to the overall health of a patient. Regardless of who is speaking, the chasm in maternal outcomes between black and white women is vast.

In New York City, black women are 12 times more likely to die as a result of childbirth than white women, according to a New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene report. This can, in large part, be attributed to the quality of hospitals that black women are giving birth in. A study by Dr. Elizabeth Howell in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, found that black women are much more likely to give birth in hospitals with higher rates of Severe Maternal Morbidity.

“All of the hospitals in central Brooklyn are at fault,” said Dr. Leslie Farrington, retired Ob-Gyn and co-leader of patient’s advocacy group, A.S.K. For Your Life. “The reason that there is such a big difference is because the care has improved for white women, because the hospitals taking care of mostly white women have improved their care.”

While that racial disparity is less pronounced nationally, black women are still dying at a rate 3-4 times higher than white women, according to CDC data. While this may look like a step in the right direction, maternal deaths have doubled nationally in the last 35 years from 7.2 deaths per 100,000 births in 1987 to 17.3 in 2013.

From 2011-2013, the most recent available data, 2,009 women died as a result of childbirth nationally. Of those 2,009 women who died while giving birth, approximately, 1,240 of them were black. And that doesn’t even begin to cover the women who require life saving interventions and survive. “For every maternal death, 100 women suffer a severe obstetric morbidity, a life threatening diagnosis or undergo a lifesaving procedure during their delivery hospitalization,” wrote Dr. Elizabeth Howell in an article this summer about maternal morbidity and mortality disparities 2017 the Seminars in Perinatology journal.

With mounting evidence on just how pernicious racial disparity in medicine is, groups have taken different approaches to address the issue. On a Saturday morning in October, twenty-plus women and two men packed into St. George’s Episcopal Church in Hempstead for a workshop on how to demand the best possible care from doctors. A.S.K. For Your Life, a New York-based organization, works to educate patients to advocate for themselves in a medical system they believe to be racially biased.

“We’re not fixing the policies or the structural racism, but what we’re saying is that we’re empowering the individual to take more control of their health by the communication techniques we teach,” said Farrington. The group has only been around for just over a year, but with regular educational workshops they’ve spoken at nearly 250 events.

Oscar Bruce, a recent college graduate and A.S.K. For Your Life’s one employee, led the workshop along with retired nurse Beverly James, the organization’s other co-leader. Coaxing attendees out of their chairs with jokes, the pair got a reluctant audience acting out doctor/ patient interactions hoping to instill attendees with confidence going into their next doctor’s appointment. The group emphasizes the importance of research before attending any doctor’s appointment, teaching patients to ask questions, and bringing a friend to all appointments as an advocate. Ultimately, Farrington and James hope that these workshops will help patients actively engaging in decision-making with doctors.

Within hospitals, efforts to close the gap are less likely to address racial bias head-on, instead focusing on medical conditions they believe to be contributing to disparate outcomes. In 2013 the American Congress of Obstetrics and Gynecology founded their Safe Motherhood Initiative. At that time, New York State ranked 48th out of 50 states for maternal mortality, and SMI had just discovered that the average patient dying as a result of childbirth was a 26 year-old, African American woman on Medicaid with a high body mass index and hypertension. Since those initial findings, the organization has held quarterly meetings to improve responses to the top three causes of maternal mortality: hemorrhage, venous thromboembolism (blood clots), and hypertension.

In an effort to diminish these three causes of maternal morbidity, SMI has developed “safety bundles” or checklists to standardize responses and remove the decision-making from doctors and medical staff during and adverse medical outcomes.

“It doesn’t matter that your patient is black or white, it doesn’t matter their insurance status,” said SMI New York district chair Dr. Iffath Hoskins. “I want to believe that in ACOG, even though I don’t know if we set out to do it initially, that it is the gold standard. She should have the expectation that when ‘I go for obstetrical care anywhere in New York State, I’m expecting that I will come out alive and healthy with my baby alive and healthy.’”

Both the Safe Motherhood Initiative and other groups such as the Society for Maternal Fetal Medicine believe that their education initiatives have made a difference. As of 2017, New York State now ranks 30th for maternal mortality in the United States with 94 percent of hospitals in New York taking up SMI recommendations to some degree. However, that glimmer of hope in improving maternal outcomes is under threat. SMI which was originally funded by Merck, will run out of funding this year.

Still, for some, like Beacon-based doula Denise Bolds, host of the podcast Birthing While Black which discusses empowerment and the risks black women face during childbirth, nothing being done so far to eliminate the gap in health outcomes goes far enough.

“The disparity is being ignored. It’s one study after another when someone wants to write a grant they gather new statistics,” said Bolds. “And we don’t need new statistics we need solutions.”