BROOKLYN – Newtown Creek in Greenpoint forms a 3.5 mile-long border between Brooklyn and Queens filled with some of the most heavily polluted water in the United States. Decades worth of pollution has been poured into the creek; raw sewage, industrial waste and an estimated 30 million gallons of crude oil from a 1978 ExxonMobil spill that ranks as the third largest oil spill in the country; three times larger than the infamous Exxon Valdez. It is hardly disputed that such toxins have been seeping under the soil in Greenpoint, a contamination area that a 2007 EPA report estimated may cover more than 100 acres. The New York State Department of Health found no oil in Greenpoint’s soil nor harmful industrial vapors present in resident’s homes; a claim that many residents have firmly disputed for years.

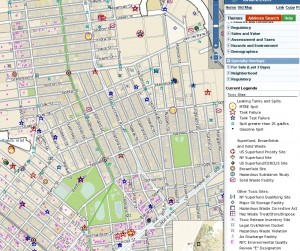

In January of this year a coalition between LaGuardia Community College and Mount Sinai Medical Center known collectively as the Health Outreach Program & Environmental Survey (HOPES) proposed a comprehensive map of Greenpoint’s most highly toxic areas. The study would identify any intensely concentrated occurrences of specific respiratory, autoimmune, heart and brain diseases. Although other such “toxic maps” exist for the area; residents say the data is skewed due to the relocation of many longtime residents and the difficulty linking together the many different illnesses that may be a result of the same toxic environmental conditions.

Over the years, Laura Hofmann, a longtime resident and activist who is involved with the HOPES proposal, has observed countless close family and friends becoming ill with eerily similar symptoms. “By the mid 1990’s, my jaw kind of was dropping at the amount of people that I knew and the extent of issues that I knew about in the community,” Hofmann said. Her knowledge of prevalent cases of autoimmune disease and brain disease coincided with an increased involvement with environmental causes; encouraging her to connect the dots. “Everywhere you go in the community, the land is either a Brownfield, a Superfund site, or has some kind of contamination from years ago. It may be prettied up, but it’s not cleaned up yet.”

Hofmann believes that previous health studies were improperly conducted and thus have produced inadequate results. “The New York State Department of Health has been very resistant. They’re not willing to do a door-to-door survey. They’re not willing to do cluster studies. They’ve claimed all along that it wouldn’t help, that it wouldn’t reveal anything,” she said. She pointed to the story of a lifelong Greenpoint resident who was diagnosed with brain cancer while living in the neighborhood and then died in a different state. Due to the geography of her death certificate, her condition would not be included in any local health studies. “They fail to connect the dots with the ailments that happened with Greenpointers over the years and the chemicals they were exposed to,” she said.

Marcy, a Greenpoint mother who refused to allow her last name to be printed to protect the privacy of her family, moved to the neighborhood with her two kids in 2007. She consulted several existing toxic maps, one of which indicated the relevant quadrant of the neighborhood to be clear of problematic indicators such as a history of tank failures, gasoline spills or a known area of MTBE spillage – a common gasoline additive with a history of leaking into and polluting groundwaters. “Per this map and similar ones we had felt we had done our homework. We thought we were okay,” she said. Both kids have developed allergies that first appeared during their time living in Greenpoint; Marcy and her husband have experienced rashes and eczema, which is a mild autoimmune disease. Her eldest child, who is special needs, has developed a serious and incurable autoimmune disorder that requires constant care. When Greenpoint’s sludge tank demolition began, all family members struggled with air quality and constant coughing, sneezing and illness. “Did Greenpoint cause the problems by pushing things over the edge with environmental toxins or more? Maybe. We need more information to know,” she said.

HOPES has been invited to submit a full, formal proposal to the Greenpoint Community Environmental Fund (GCEF); the organization that manages the $19.5 million won by the State of New York in a settlement with ExxonMobil. There will be a community review process, followed by a independent selection jury that will determine any allocation of funds.

Calls to GCEF for comment on the status of the proposal were unreturned at press time. Should their requests be granted, Marcy insists it will be money well spent.

“I thought I did my homework over 7 years ago but now I know I didn’t have the information I needed to make a truly informed decision,” she said. “We love Greenpoint but we may have not come here had I known what I know now about the environmental stuff. Everyone deserves this knowledge”.