New York City’s slowly declining unemployment rate has stalled at 8.7 percent since March, leaving more than 340,000 New Yorkers currently searching for work. According to the New York State Department of Labor, more than half of the unemployed New Yorkers are either Hispanic or black.

Pedro Mercado is one of the roughly 140,000 Hispanics who are struggling to make ends meet as the unemployment rates and job opportunities continue to fluctuate. On an average day, Mercado spends more than 10 hours standing near Roosevelt Avenue in Queens with dozens of other day laborers next to him, hoping to find work so that he can send money to his family in Mexico – or to simply survive.

Day laborers like Pedro Mercado have been hit hard by the lack of work in the city, and are unable to collect unemployment benefits like some unemployed New Yorkers.

When times are good, Mercado has what he calls a “good week,” and is able to send up to $200 to his wife and three kids in Mexico. Unfortunately, the last time Mercado had a “good week” was almost four years ago.

“I went from working five or six days, and maybe one rest day, to waiting around seven days and praying I find work,” said Mercado in Spanish. “The little money you do make you use to survive, but even then it’s usually not enough. Every day you wonder, ‘am I going to have money to survive?’”

Mercado, 36, came to the U.S. in 2006 when his family lost their home in Mexico. His wife and kids moved in with her parents, while he came to the U.S. in search of a job that would allow him to send money back to his family. When he arrived, finding work was not easy, especially since he did not know English. An acquaintance introduced him to the life of day laboring, and he has been doing it ever since.

In late 2006, Mercado began day laboring – standing on corners along Roosevelt Avenue and 69th street, waiting for anyone with a job offer. Taking on a wide variety of low-paying jobs that ranged from moving furniture to painting houses, Mercado would earn roughly $60 a day – just enough to pay his bills. Today, he spends more time waiting and looking for work than actually working, and takes home maybe $80 a week.

“Look around, it’s not just [day laborers] who can’t find work,” said Mercado, who earlier this year went six consecutive weeks with no work. “I meet people who had steady jobs for many years and they stand next to me every morning looking for work, but the hard truth is that there is no work.”

In 2006, New York City’s unemployment rate hit a record-low 4.1 percent, according to the State’s Labor Department. Over the past five years, however, the unemployment rate has doubled, reaching a decade-high 10.3 percent in 2009.

During these tough economic times, many New Yorkers have been forced into jobs they never imagined doing. Corona-native Jamal Cooper worked as a porter in Astoria for six years until he was laid off in January. As a result, Cooper resorts to cutting hair from his kitchen, hoping to save enough money to one day open up a barbershop of his own. To “scrape a few more bucks together,” he also goes to local barbershops and offers his cleaning services for a small charge.

Cooper has applied for countless jobs and been on half-a-dozen interviews, but has had very little success. While he considers himself fortunate to be receiving unemployment benefits, he says the funds barely cover his rent, let alone other living expenses. He is also worried that he won’t find a new job before his unemployment benefits run out.

“I do whatever pays the bills honestly, people are desperate,” said Cooper. “When you have no job, it’s up to you to make something happen. There are too many people who are in the same position [with no job], so every little cent you can make really helps.”

Alan Perez, 25, was a waiter at a restaurant on Roosevelt Avenue who now works as a soccer instructor. This may sound like a step up, but he is making less money coaching then when he was waiting tables. Perez lost his job at the restaurant in August 2010 when it was sold and shut down suddenly and turned into a hair salon. He spent six months unsuccessfully looking for another job, forcing him to leave his apartment in Jackson Heights and move back in with his parents. In February, while buying coffee for his father, Perez coincidentally bumped into his old soccer coach, who was looking for new assistants. Perez snagged a part-time job as an assistant coach – making $30 a day, 4 days a week.

In his spare time, Perez continues to apply to countless job listings, hoping to find more steady work.

“I never thought I’d be living with my parents again,” said Perez laughing. “I’m thankful for the job I have now. I know things could be worse, but I really need to make more [money]. These are really tough times for Latinos living in the U.S. – especially if you’re living with your parents.”

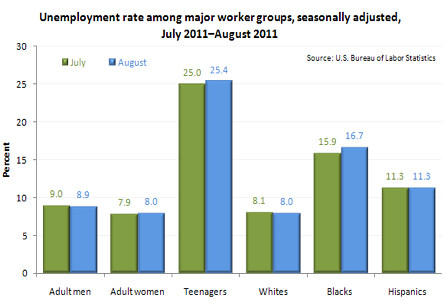

In the U.S., Hispanic and African Americans account for more than 5 million of the 14 million unemployed Americans. Hispanic Americans have a national unemployment rate of 11.3 percent; second only to blacks among all minorities whose unemployment rate is 15.8 percent, according to the monthly report released by the Bureau of Labor Studies in September. The national unemployment rate is currently 9.1 percent.

In New York City, Hispanics and blacks make up half of the work force, but account for three-fourths of its unemployed, according to City Comptroller John C. Liu. The city’s unemployment rate for Hispanics was 13.3 percent in 2010, and 15.3 percent for African Americans. By comparison, for the year 2010, the unemployment rate among whites was 5.2 percent.

“Jobs are vital to everyone regardless of race, age, or zip code,” said Comptroller Liu in a statement. “Persistent inequities in unemployment threaten the economic health of the City as a whole. It’s important that the City economy works for everyone, so the crisis like the one we’ve seen doesn’t happen again.”

Figures show that the city’s unemployment rate is slowly improving since the recession began in 2008, displaying a decrease in unemployment rate from more than 10 percent in 2009, to 8.7 percent today. The large majority of unemployed New Yorkers are eligible to receive unemployment benefits up to a maximum of 93 weeks to alleviate the financial burdens they may be facing, according to the Department of Labor. Unfortunately, many sectors of the economy – including waiters, nannies, day laborers, house cleaners, and some other off the books service workers – are typically ineligible for aid, and it is this low-paying economy that is often dominated by minority workers.

But even for those lucky enough to receive unemployment benefits, the aid is no replacement for a paycheck. In the meantime, the jobless, like Cooper, Mercado and Perez, will continue to wait for better days.

“All I can do is wake up every day and hope I find work because if not, what else am I going to do, give up?” Mercado said. “I can’t do that – I have a family and they need me to work. Now.”